Many wrote streetwear off as a short-lived trend, reducing it down to sneakers and hoodies, which eventually people would get bored of and move on, like they do with everything else in fashion. But streetwear has become one of the most disruptive forces in modern retail. And its success largely comes down to one thing: hype.

Recognizing this, brands far and wide are taking pages out of streetwear’s playbook. Brooklyn-based MSCHF, for example, has been dropping some of the most viral (and out-there) products you’ll find anywhere online over the past few years. No surprise, then, that people are calling MSCHF ‘the new Supreme’. The brand’s only post on LinkedIn describes it as a dairy company, while its CEO, Gabriel Whaley, refuses to offer any kind of definition, but says MSCHF runs on ‘structured chaos’.

There’s no obvious thread connecting MSCHF’s abundance of projects, but it’s definitely not a dairy company. It has designed more than 50 products to date – among them, a squeaking rubber-chicken bong for smoking weed; ‘Birkinstock’ sandals made using the leather from real Hermès Birkin bags; a Chrome plug-in that lets you watch Netflix at work by hiding it inside a fake Google Hangouts chat; and the unofficially modified Lil Nas X satan-themed Nike sneakers that retailed for $1,018 (since notoriously recalled as part of settlement with the sportswear giant). Despite limited publicity, MSCHF frequently sells out of its products.

‘The products are devious and always push things to the extreme,’ says Raihan Anwar, who co-founded token-driven social network Friends With Benefits and is also launching the world’s first meme marketplace later this year. As someone fluent in online culture, he remembers some of MSCHF’s earliest drops. ‘They had a very short shelf life but at the same time they burned super hard, sucking all the oxygen out of the room. The people who follow MSCHF know that the joke is on them, but they’re in on the joke. The future of the web is going to thrive on hype, and MSCHF understands this as well as anyone.’

Raihan points out that even brands like Peloton, which sells at-home exercise equipment, have become ‘oddly good at hype. Peloton, with all its new classes and instructor and content dropping, has basically mixed SoulCycle with the hype business model.’

Increasingly, hype is taking on a life of its own. It has become a primary metric by which anything is judged. ‘Often, the actual product doesn’t bear much relevance to the marketing of it,’ says former Vice reporter Gabrielle Bluestone, who writes about online culture and has a new book out called Hype. ‘But for most people, that doesn’t seem to matter any more.’

Financial journalist Felix Salmon goes one step further. ‘If you want to understand the world we live in, look to the hypebeasts, not the Wall Street Journal,’ he wrote in Wealthsimple Magazine in March of this year. So, read on for 10 things to keep in mind when dealing in the business of hype.

1. Drops

Drops – limited-edition product releases, usually every week or two, both online and in physical stores – have always been Supreme’s way of doing things. The New York-based apparel and lifestyle brand pioneered this sales tactic that is now copied by all the biggest players in streetwear, as well as the likes of luxury brands Burberry and Gucci. In fact, most major fashion brands have developed drop strategies by now.

What’s new is how drops are starting to extend to industries that have nothing to do with clothing. Travel agency HotelTonight has a ‘Daily Drop’ feature on its app giving users 15-minute windows to access huge discounts. Other travel companies have recently started following in its footsteps.

The drop has become such an important part of how we shop today that even luxury watch brands – which were painfully slow in moving from selling watches IRL to online – have introduced them. Ben Clymer, founder of Hodinkee, a luxury watch and lifestyle website, says: ‘The drop method is definitely in vogue right now – and it’s not just the new watch brands jumping on it; it’s the legacy brands, too. Drops are achieving great results all across the industry.’

It’s not hard to imagine drops coming soon to other on-demand applications, particularly in the categories of food delivery, event booking and maybe even online dating. In the new reality of retail, it’s all about the time-limited offer. If legacy watch brands can pull it off, anyone can.

2. Irony

Today, irony is everywhere. Felix Salmon calls it ‘the dominant mode of Extremely Online culture’. ‘The less sense a value proposition makes, the more ironic it becomes,’ he writes, ‘and the more ironic it becomes, the more attractive it becomes.’

Hypebeasts – devotees of fashionable items – hoovered up Vetements’ £185 DHL T-shirts in 2016. When Supreme started selling clay bricks for $30 the same year, people lost their minds; after they sold out, within minutes they started selling on eBay with price tags of $1,000. These products are successful not despite the fact they’re ridiculous, but because of it.

The tradition of ironic objects being worth big money goes back a long time – look at artist Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 urinal – and, now that ‘ironic consumption’ has become such a thing, there are even academic papers on it – all because the streetwear industry has made it almost normal.

Lately, brands in other sectors have been following suit. Recess, which sells sparkling water infused with CBD and adaptogens, spins ‘millennial nu-irony for likes and sales’, according to the New York Times. ‘The product and marketing exist within the general boundaries of detached and ironized millennial sentiment.’ More brands in various sectors should think about doing the same.

3. Scarcity

James Jebbia, Supreme’s founder and CEO, rarely gives interviews but, in 2009, he said: ‘If there’s demand for 600, we’ll make 400.’ Limiting product supply amid high demand goes against one of the most basic principles of economics. Then again, the 27-year-old brand, inspired by hip-hop and skate culture, has always done things its own way.

While Supreme has achieved huge success – in 2020 it was acquired for more than $2 billion – the main question surrounding streetwear and the hype business model has always been whether it is sustainable. Maintaining exclusivity through limited drops is hard when you’re looking to grow fast; after all, flooding products into the market is usually an easy way to produce sustainable growth. But if hype brands set up more shops, increase production and meet all existing demand, their exclusivity becomes at risk. If everyone has it, nobody wants it. Scarcity is what defines them.

Sometimes, then, less is more. But finding the sweet spot of maximum profits with the right production levels isn’t easy. One way streetwear brands get around this is to release lots of different products, but very few of each one. ‘Although the scarcity model isn’t new, it was perfected by streetwear labels,’ says Lois Sakany, co-founder and editor of fashion website Snobette. As such, products remain exclusive, desirable and expensive. On scarcity, Gabrielle Bluestone adds, ‘As a result of the FOMO [fear of missing out] loop, we’re more likely to buy into something blindly.’

4. Resale

When Nike first dropped the Air Jordan 1 in 1985, the sneakers sold faster than the company could manufacture them. Official retailers started selling the small amount of stock they could get their hands on for more than Nike’s $64.95 recommended retail price. These same sneakers were then bought by other retailers who, in turn, charged higher prices. As such, the sneaker resale economy was born.

The market started to grow faster in the mid-nineties when eBay brought non-retail sellers into the game. But nothing like what we are seeing today: last July, financial services company Cowen Inc estimated that sneaker resale was worth $2 billion in North America alone. ‘Sneaker authenticator’ is even a job title at the world’s biggest multimillion-dollar reselling companies, like Stadium Goods.

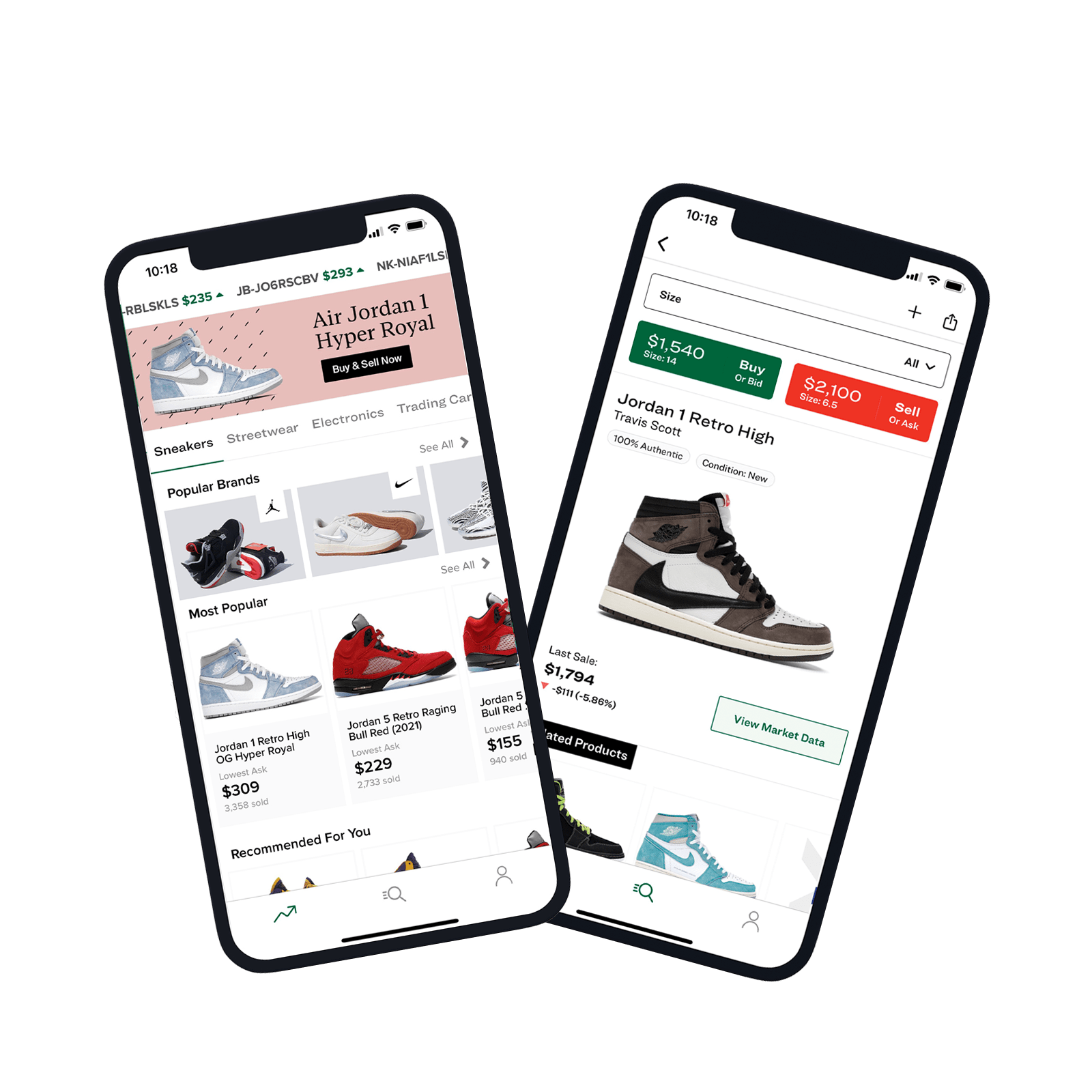

The ultimate middleman facilitating the flow of sneakers, though, is StockX. In 2014, when co-founder Josh Luber was a consultant at IBM with a sneaker blog on the side, he said the secondary market for sneakers was ‘more similar to the illegal drug trade’ than a stock exchange. Two years later, he launched StockX to put that right.

Of the biggest sneaker brands in the world, Nike is the best at leveraging the benefits of the resale economy. According to Highsnobiety’s 2021 Sneaker Report, Nike took a completely different approach to the likes of Adidas in the first quarter of 2021, by releasing far more sneakers than any of its competitors (‘an absolutely mind-boggling number’), partly because it knew the brand was performing so well on resale platforms like StockX.

‘The share of hyped sneakers (defined as sneakers reselling for at least 50% over retail) was remarkably high,’ says the report. ‘Around 50% of all Nike sneakers that were released in Q1 and were available on StockX have a price premium of 50% or more.’

Analysts say the resale economy isn’t going away any time soon, and those at the biggest reselling platforms agree. If anything, the resale economy is expanding beyond sneakers. ‘Resale as a whole was already growing globally, but we’ve been seeing the market begin to mature as the idea of resale is moving beyond sneakers,’ says Eddy Lu, CEO and co-founder of GOAT Group, the parent company of the sneaker and luxury clothing marketplace. ‘Gen Z and millennials make up 80% of GOAT’s customers today, and are much more comfortable with resale than previous generations.

‘These younger consumers are gravitating towards unique pieces and are mixing high and low, new and used products to create a style that helps them stand out,’ he continues, before adding that GOAT is one of the few luxury and lifestyle platforms that sells new and used clothing and footwear in the same place. ‘This is how young consumers are choosing to shop now.’

The watch industry has again been quick to jump on this particular streetwear sales tactic. Take Subdial, one of many online watch retailers these days, whose co-founder Ross Crane says, ‘Business tripled last year – maybe it will slow down, but it feels sustainable.’ He puts a big chunk of the watch industry’s recent success as a whole down to the secondary resale market that has bubbled up in recent years. ‘It would be a much, much smaller market without it. Resale has thrown the industry a lifeline. People are nuts about watches. They always have been. Only now there are even more independent, imaginative and modern brands uncovering new ground and creating new experiences for them.’

05. Deadstock

Deadstock – or unsold goods – usually ends up costing businesses a lot of money (first in lost profits, second in storage costs). But the sneaker and streetwear industries have found a solution. In these niche sectors, it turns out that even deadstock has value now.

On platforms like StockX, resellers make a virtue of when products are discontinued, racing to buy them all up and waiting until demand rises again. Then they emphasize that the styles are rare – that they are no longer made – and come with all of the original packaging. Owners of Nike deadstock, for example, made a lot of money when Netflix released The Last Dance, a 10-part series about Michael Jordan’s final season with the Chicago Bulls, which made many unfashionable sneakers popular again.

The general shift away from sales in bricks-and-mortar stores to online has also helped. Whenever there’s a markdown in the price of a shoe – nicknamed a ‘brick’, after a missed shot in basketball and supposedly reflecting the way a shoe stays weighed down to store shelves when it won’t sell – bots snap them up so quickly that regular consumers don’t even notice they’ve been discounted. Bots take advantage of discount codes, often earning up to 40% off orders. On resale platforms, ironically, the shoes frequently earn up to 30% more than the original sale price.

The first deadstock marketplace for sneakers and streetwear, Deadstock App, launched on 15 July. It’s unlikely to be the last. And before long, other industries will look to do the same.

6. High prices

Way back in 1899, economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen coined the term ‘conspicuous consumption’, pointing out how consumers spent on expensive goods because of, not in spite of, their high prices. In other words, people look to blow large amounts of money on products when they boost social status in an obvious display of affluence. Little did the Norwegian-American know that he had outlined the business model for the biggest hype brands more than a century before they came into existence.

7. Community

According to Highsnobiety, ‘The 2010s were the decade luxury and streetwear became one.’ The observation isn’t new: every streetwear fan has noticed how brands in this space churn out the same kinds of products they always have, yet increasingly charge higher and higher prices.

The reason they can do this is partly down to the huge communities they’ve built online, mainly through social media. As Felix Salmon writes, ‘To create value in an object is just to create shared agreement about that object’s value. The larger the community in agreement, the more value that can be created. The communities that can be built online are almost limitless in size, which means they can create value at will.’

The internet has accelerated and intensified the way communities align themselves around brands. And streetwear brands were quick to see that the pendulum won’t be swinging back. ‘It’s becoming less about the actual products,’ says Gabrielle Bluestone. ‘It’s really about the hype being amplified by social media. In turn, this helps brands form an engaged community.’

8. Raffles

Snobette’s Lois Sakany says, ‘The streetwear space is ever-shifting, and the brands generating hype and excitement are very different now versus even five years ago.’

New sales tactics such as raffles are central to this. They were introduced to handle the release of new products when demand exceeds supply. To make the process fair, streetwear brands claim – tongues firmly in cheeks – that ticket numbers are picked at random and given to customers; if your number is drawn: lucky you, spend away.

‘Raffles grew out of Nike’s limited-edition launches of its most coveted sneaker silhouettes,’ says Lois. ‘Then sneaker boutiques turned to them in an attempt to create a fairer system than a first-come-first-serve physical store model, which became impossible during the pandemic.’

In reality, things played out rather differently. Bots that automate the process of buying a new product the instant it becomes available online have taken over. Non-bot-using customers hate them because it’s almost impossible to check out faster than a bot can. Frequently, one or two bots buy up a large chunk of the product simply to resell it – a poor customer experience for everyone. Brands are aware of this but carry on with raffles because, in many ways, it keeps feeding the hype cycle. Around and around we go.

09. Waiting lists

In recent months, brands from non-streetwear sectors have started introducing raffles, as well as online waiting lists (another sales tactic taken straight from the streetwear playbook) in an attempt to emulate the snaking outdoor lines synonymous with drop culture.

Headlines along the lines of ‘This T-shirt hasn’t even shipped but has a 3,000-person waitlist’ are no longer surprising. Brand loyalty is something for companies to brag about – as well as newsy clickbait for publishers and added hype. Waitlisting products or being a part of the waitlist makes you feel like you’re getting something that’s coveted. It’s another sales tactic you should expect to find its way to other industries soon.

10. Balance

In her book, Gabrielle Bluestone points out that hype relies on ‘plain human psychology’ and the ‘science of anticipation – what happens to us when we anticipate a pleasurable event, the role dopamine plays in how we respond when we’re emotionally connected, and how our brain chemistry can be easily manipulated.’

But there’s a flip side: too much hype can lead to no hype at all. Academic researchers have a term for this – ‘affective misforecasting’ – and use it to describe the gap between the anticipated experience and the actual experience. To that end, keep in mind that creating hype is a delicate balance. No one said any of this would be easy.

This article was first published in Courier issue 43, October/November 2021. To purchase the issue or become a subscriber, head to our webshop.